(Photo courtesy Betty Griffiths)

Rarely a day goes by that the Restore Oregon office doesn’t get a panicked call about the demolition of an older building somewhere in the Willamette Valley. As the economy rebounds across Oregon, permit data from the state’s larger cities are confirming what we’ve been hearing for the past year: a lot of buildings are coming down.

In Portland, a 1908 Western False Front building in Linnton is being readied for demolition with no approved plans for new construction on the site.

In Corvallis, a 1912 farmhouse was razed over the summer with intent to replace it with a faux-replica.

In Salem, a 1947 Pietro Belluschi-designed bank will soon come down to make way for a vacant lot in the heart of downtown.

In Eugene, a Tudor clubhouse from the ‘20s was removed to pave the way for a student housing complex.

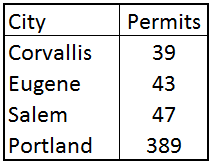

received in 2013. Because

of technicalities, the total

number of buildings all

but demolished in

2013 is much higher.

While demolition of older buildings certainly isn’t a new phenomenon in Oregon, the past year has ushered in a significant uptick in demolitions. In 2013 alone, 279 residential buildings applied for demolition permits in Portland—double the number of house demolitions from just three years ago. On the commercial side, 110 income-producing buildings (apartments, storefronts, offices) across Portland were approved for demo in 2013. Corvallis, similarly, has faced immense development pressure over the past two years due to a spike in demand for student housing and an apartment vacancy rate around one percent. Of the 39 demolitions in Corvallis last year, 14 were older and historic single-family houses. While 14 may not sound like a large number, their loss—and the suburban-style infill that has replaced them—has had a dramatic effect in the neighborhoods adjacent to Oregon State.

Recent demolition permits, while sizable in number, don’t tell the full story. According to Shawn Wood, Portland’s Construction Waste Specialist, “Residential demos don’t include ‘remodels’ that all but demolish the structure. If one were to consider removing a building down to the foundation wall a demolition (which our permitting does not) the residential numbers would increase significantly.”

While motives for demolition range from construction of Modern mcmansions and faux-historic palaces to apartment complexes and mixed-used developments, the recent demolition trend means we can expect hundreds of buildings to go into Oregon landfills again this year.

Why Does the Demolition Trend Matter?

While vacant and neglected buildings are not uncommon candidates for demolition, many (if not most) recently-demolished buildings were occupied and functional prior to their removal. With few exceptions, virtually none of the buildings demolished in Oregon’s larger cities in recent years were officially designated on the National Register of Historic Places (preservation ordinances typically include provisions to delay or deny demolition of designated historic buildings). So, if the buildings aren’t capital H “Historic,” why does this trend in demolitions cause us concern?

Erosion of Neighborhood Character and Community Culture

North and Northeast Portland (Photo

courtesy Karla Pearlstein)

As showcased in a recent Oregonian article, tensions between demolition-minded owners and neighborhood preservationists are rising in older, established neighborhoods. Because design review isn’t required in most established neighborhoods, much of the new construction that follows the demolitions is not compatible with the character of the neighborhood around it. According to the Oregonian, “ aren’t required to make neighbors happy… As long as developers abide by the code, the design is at their discretion.”

While most of the buildings recently demolished in Oregon’s larger cities weren’t listed on the National Register, that isn’t to say many of them weren’t significant. Last year, we threw away countless buildings that were well-designed, compatible with their surroundings, and told the stories of previous generations. The average residential building demolished in Portland in recent years was built in 1927.

“Retaining the integrity and continuity of traditional neighborhoods is a significant concern for Restore Oregon,” says Executive Director Peggy Moretti. “We need to be careful that in the name of density, we aren’t sacrificing quality, character, and our unique sense of place. Without thoughtful urban planning and community involvement, some of Oregon’s most livable neighborhoods could be lost in the next ten years.”

Environmental Impact of Demolition Waste

Portland, demolished in early 2013 (Photo courtesy

Doug Decker/alamedahistory.org)

Preservation economist Donovan Rypkema often asks the question, why recycle cans and bottles and throw away entire buildings?

The current tear-down trend across Oregon should cause pause for any environmentally-conscious Oregonian because the demolition of buildings amounts to a staggering amount of embodied energy that is literally being thrown away. Every time we raze an older house and replace it with a new, more energy efficient one, it takes an average of 50 years to recover the climate change impacts related to its demolition.

So, how does demolition compare to recycling those cans and bottles? In short, recycle happy Oregonians might be in for a shock.

Let’s look at Portland’s demolition waste last year. We know the typical demolished house is 1,200 square feet and generates 115 pounds of demolition waste per square foot, of which 60% is recycled and 2% is salvaged. In terms of weight, landfilling the 279 houses that applied for demolition permits in 2013 was the equivalent of

- 438.9 million aluminum cans (728 per Portlander), or

- 33.4 million glass beer bottles (55 per Portlander), or

- 1.5 billion pieces of copy paper (2,426 per Portlander)

…and that doesn’t even include Portland’s 110 demolished commercial buildings or residential tear-downs that called themselves “remodels.” According to a recent national study, “If the city of Portland were to retrofit and reuse the single-family homes and commercial office buildings that it is otherwise likely to demolish over the next 10 years, the potential impact reduction would total approximately 231,000 metric tons of CO2 – approximately 15% of total CO2 reduction targets over the next decade.”

The opportunity cost of trashing this much embodied energy is staggering for a place that is often considered the nation’s greenest.

What Should We Do About It?

The staff at Restore Oregon know that not every older building is historically significant or deserving of preservation. But the community, cultural, and environmental impacts of the increasing demolition trend deserves serious consideration as the population of Oregon’s larger communities continues to grow and close-in neighborhoods are favored by developers and planners to absorb the density needed to keep urban growth boundaries constrained. So what can we do to appropriately manage tear-downs?

buildings in neighborhoods most impacted by

demolitions (Photo courtesy Amanda Cowan/

Corvallis Gazette-Times)

Document What We’ve Got

In order to understand which buildings and districts are eligible for the National Register and the local protection that comes with designation, historic resource surveys should be conducted on regular intervals. However, many of Oregon’s cities have not updated their historic resource inventories since the 1980s and have an inadequate understanding of the potential significance of buildings that are being demolished. Following Corvallis’ lead, cities and neighborhood advocates must conduct surveys to know what’s out there in order to know what’s worth protecting.

Institute Public Review of Demolitions

Each city handles demolition permitting a little differently. In Eugene, projects pursuing a building permit for new construction in tandem with the removal of an existing building do not require a separate demolition permit. Portland waives neighborhood notification requirements if a property owner applies for a new building permit at the same time as the demolition permit. A decade ago, Ashland created a three-member panel to review demolition applications, however, that review process has gone by the wayside. Outside of Oregon, some cities and states require demolition review of all buildings older than 50 years.

Provisions that require review or delay of demolition applications allow time for the public to identify alternatives to the loss of buildings worthy of preservation. Even if a building is destined for demo, review can incentivize salvage and documentation where appropriate.

Change Local Zoning

Many of the buildings demolished in recent years were scraped to make way for denser development allowed by the local zoning code. When zoning allows for new construction that is significantly larger than the existing buildings, it entices owners to sell-out because of the speculative increase in property value. In order to prevent unwanted demolitions, local leaders must ensure the zoning corresponds with the vision and themes of unique districts. Additionally, design guidelines and standards (such as those recommended by Restore Oregon for historic districts) would help narrow the market for new construction to what is desired by a community.

Tax Landfill Waste

Since the amount of waste resulting from demolitions is staggering, cities should consider landfill taxes or increased permit fees to mitigate for the loss of embodied energy in existing buildings. If, in fact, “the greenest building is the one that already exists” then we should disincentivize their demolition.

prepared for demolition in this January 24,

2014, photo. Despite being listed in the

Historic Resources Inventory and cited as a

prime example of the Eastlake Style in Classic

Houses of Portland, the house had no formal

protection to slow or stop the demolition permit

request (Restore Oregon Instagram photo).

Remove Hurdles for Relocation

It’s always best to keep a historic building on its original site. But when that’s not possible, communities should make emergency relocation easier. As demonstrated by the recent move of the Rayworth House in Portland, bureaucratic hurdles can stymie worth-while efforts to relocate existing buildings faced with demolition. Especially for those well-built houses found along our rapidly-densifying Main Streets, cities should adopt programs to make relocation feasible in cases of imminent demolition. Policies that encourage salvage as a last resort should be codified to boost the paltry recycle and reuse rate of buildings being demolished today.

Neighborhoods and Main Streets change over time, and the demolition of existing buildings will always be an undeniable component of that change. The densification of Oregon cities is a laudable goal that will preserve farmland and add amenities to neighborhoods and business districts. However, older buildings that have historic significance, aesthetic character, and embodied energy worth preserving should not be prime candidates for clearing a path towards densification and change. We need to begin appropriately weighing the impacts of building demolition to foster a gentle densification that retains the best existing resources, while still meeting planning objectives for our evolving communities.