Water has been a hot topic on the West Coast as drought declarations have moved north from California into Southern and Eastern Oregon. With all of this talk, why not take a quick look back at Portland’s water history?

Beginning in the mid-1800s, water was first supplied to the city of Portland from creeks in the West Hills and Portland Heights. As the city grew, reservoirs were built and water was eventually sourced from the Bull Run watershed near Mt. Hood. Today, Portland’s water system is on tap to undergo one of its largest changes since the 1890s. Over the span of 150 years and many technological changes, Portland has been able to retain the histories of these utilities so that the city’s water stories can be told to future generations.

Here is a Whitman Sampler of Portland’s historic water resources, past, present, and future.

Balch Creek Dam

One of Portland’s earliest water sources was Balch Creek near today’s Forest Park. Named after pioneer and scandalous criminal Danford Balch, Balch Creek was sold to the Portland Water Works in 1864 so the watershed could supply part of Portland’s water needs. With pipes connecting the creek to the growing city, this water supply operated until 1890s. Remnants of the concrete and steel dams once used to harness the water are still visible under the Thurman Street Bridge. Today the creek is an integral part of Macleay’s Park, with a plaque erected to honor the creek’s importance in the development stages of the city’s water supply.

Lincoln Street Reservoir

Lincoln Street Reservoir

During the later years of Balch Creek providing water to the city, a reservoir was built in the vicinity of Southwest Lincoln Street to store and supply water to the area that is now Portland State University. A small brick gate house was built in 1890 to pump water to residents at higher elevations. Between a shortage of creek water and the construction of larger reservoirs at higher elevations in the 1890s, the reservoir and gate house were abandoned and the reservoir was eventually filled. However, the story of this reservoir can be told even today with the gate house still standing on SW 10th avenue, hidden amongst new development.

Mount Tabor Reservoirs

The insufficient supply of water from local creeks led to the development and construction of Mount Tabor and Washington Park Reservoirs using water piped from the Bull Run River near Mt. Hood. In 1888, Portland’s Water Commission bought land on Mount Tabor and two reservoirs were completed in 1894 (Reservoirs 1 and 2). Fifteen years later, two more reservoirs were built on Mount Tabor and, a few years after that, a seventh reservoir was built underground. Reservoir 2 was decommissioned in 1976, but its Romanesque style gatehouse, located at SE 60th Avenue and Division Street, remained standing even after the reservoir was filled. The gatehouse was abandoned until the early 1990s and was slated to be demolished to make way for new residential housing, but was instead converted into a residential house in 1993. Both the orphaned gatehouse and the remaining Mount Tabor Reservoirs are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

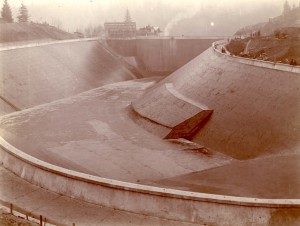

Washington Park Reservoirs

Washington Park Reservoirs

The Washington Park Reservoirs were built during the same time as those on Mount Tabor, also opening in 1894. Construction of Reservoirs 3 and 4 supplied Bull Run water across the City’s westside and led to the development of Washington Park. Reservoir 3 has a grand staircase and historic gatehouse, while the downhill Reservoir 4 has only a smaller historic gatehouse. The Washington Park Reservoirs are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

What’s Ahead?

In 2006, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a rule regulating the use of open reservoirs across the country. Because of this Federal change in how the City of Portland is expected to store water, local leaders have determined that all open reservoirs will be closed. While the process has generated much public dialogue, the plans for complying with the rule do include provisions to continue to tell Portland’s reservoir story.

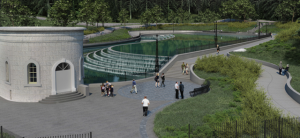

changes at Washington Park.

(Image courtesy of City of Portland)

On the westside, the Washington Park Reservoir Improvements Project proposes to build an underground reservoir in the same area as the existing Reservoir 3, covering the tank with a reflecting pool on top. Reservoir 4 will be partially restored to its pre-reservoir condition with a lowland habitat area, reflecting pool, and landslide abatement in the lowland area. Even though the reservoirs will technically be demolished, the project has been supported by the City’s Historic Landmarks Commission because of the planned restoration and interpretation of many of the site’s historic features. This is a big change from the intended purposes of the reservoirs, but will retain much of the historic look of the reservoirs and still allow them tell their story. The $76 million project will be completed by 2020.

On the eastside, Mount Tabor’s open reservoirs are also proposed to be disconnected. Even though they will no longer store potable water in their open-air configuration, the City still needs to identify a plan for how best to continue to tell the history these reservoirs. The Water Bureau’s website demonstrates the significant difference in planning for the Mount Tabor project as compared to the thoughtful compromises proposed for Washington Park. The Portland Historic Landmarks Commission has expressed concern regarding the lack of public process related to the Mount Tabor project, stating in a recent letter, “It seems irresponsible to approve disconnection of this resource from Portland’s water system—essentially rendering it useless—without having a plan or conditions that ensure its long-term care and stewardship.”

Although changes are likely ahead for Portland’s most known reservoirs, why not enjoy the wonderful summer weather with a trip throughout the city to see the historic reservoirs and learn some of the many stories they have to share?

No, the EPA did not ban open reservoirs.

Nor does it pass acts.

The EPA published a rule that requires open reservoirs to choose between treating water at the outlet or putting on some kind of cover.

That rule is only a small addendum to a greater law, passed by Congress, which also allow anyone with just cause to get a variance from a rule if water quality merits it.

However, jurisdiction over Oregon’s reservoirs now lies with Oregon, and our laws do not allow alteration of an existing structure unless it is absolutely necessary, which it is not in the case of the open reservoirs.

Read all three applicable rules and laws below, but meanwhile, please please please do not assume that just because public officials talks of a federal “ban” that makes it so. It couldn’t be further from the truth, which is why open reservoirs in Rochester and New York City are remaining open with the feds’ blessing.

Long-Term-2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule (“LT2”)

https://www.google.com/search?newwindow=1&site=&source=hp&q=long+term+2+enhanced+surface+water+treatment&oq=long-term+II+surface+&gs_l=hp.3.0.0i22i30.1039.8227.0.9496.28.24.3.1.1.1.117.2026.19j5.24.0….0…1c.1.64.hp..4.24.1727.0.uqczgqJwpDo

Safe Drinking Water Act

http://www.epw.senate.gov/sdwa.pdf

Oregon’s law on drinking water protections, ORS 448.131

http://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/448.131

Thank you, Katherin, for providing additional background on the LT2 rule. We hope readers take the time to click through some of the valuable links you have provided here. I have edited the post to better reflect accurate terminology as per your suggestion.

Thank you!

Katherin is correct! The EPA did not ban open reservoirs.

This is crucial and should be corrected ASAP. Please, in the name of journalism.

We’ve corrected the language in the post to better highlight why the City is considering closing the open reservoirs. Because of the complexity of the issues at play, we hope readers will find more background on LT2 in existing online resources.

I looked for a board of directors for this site. I did not see a tab for that. How would an interested person find the major contributors to this site? I am curious.

There is a link to Board and Advisors in the footer.

Thank you, Denise Bartelt. I found that after I posted my comment.

Thank you for the historical summary of Portland’s water reservoirs. Balch Creek and Lincoln Street provide a rich perspective before Portland went to the Willamette River in the late 1800’s. It was the contaminated Willamette River that drew Portland to the Bull Run, and then the historically recognized reservoir system we have today. The Portland reservoir system was built by Ernest Ransome far ahead of his time in engineering ingenuity. That’s why they are here today functioning as they were designed for public health benefits with over 100 years without illness. The EPA has not banned the open reservoirs, but given us options; such as covering, treating outlet and an EPA Waiver (exempting us) from regulation because we already meet EPA drinking water standards. Our elected officials have for whatever reason not acted to request or obtain the waiver that is available. New York City has been working with EPA for a waiver. We need all of our open reservoirs to keep toxic chemicals like Radon from entering our homes schools and work places. We currently are drinking radioactive Radon drinking water from the Columbia South Shore Well fields blended with Bull Run water. We need the open reservoirs to allow the Radon gas to harmlessly escape into air. The open reservoirs need to be retained.

Lydia,

Thank you for the historical summary of Portland’s water reservoirs. Balch Creek and Lincoln Street provide a rich perspective before Portland went to the Willamette River in the late 1800’s. It was the contaminated Willamette River that drew Portland to the Bull Run, and then the historically recognized reservoir system we have today. The Portland reservoir system was built by Ernest Ransome far ahead of his time in engineering ingenuity. That’s why they are here today functioning as they were designed for public health benefits with over 100 years without illness. The EPA has not banned the open reservoirs, but given us options; such as covering, treating outlet and an EPA Waiver (exempting us) from regulation because we already meet EPA drinking water standards. Our elected officials have for whatever reason not acted to request or obtain the waiver that is available. New York City has been working with EPA for a waiver. We need all of our open reservoirs to keep toxic chemicals like Radon from entering our homes schools and work places. We currently are drinking radioactive Radon drinking water from the Columbia South Shore Well fields blended with Bull Run water. We need the open reservoirs to allow the Radon gas to harmlessly escape into air. The open reservoirs need to be retained.

Lydia, while I think you provide a pretty good overview of our reservoirs, i agree with the sentiments expressed by the other comments here. It is easy for journalists and others to gloss over details and reiterate the party line offered by, in this case, the Water Bureau, which has a well documented history of wanting to get rid of our historic open reservoirs, regardless of how functional, efficient and elegant they are.

As for your current version, it seems to me it still needs to reflect in the body of your piece itself that there is and has been major objection by many stakeholders, ranging from the Mt. Tabor Neighborhood, who is the main party in the current land use appeal, to Friends of the Reservoirs and most other neighborhood associations, and Southeast Uplift, the umbrella organization for the east side neighborhood associations. And numerous other organizations and businesses.

While you have a quote from the Historic Landmarks Commission re the importance of having conditions to ensure the reservoirs are maintained properly, you are missing the key follow-up point that after the Historic Landmarks Commission ruled in favor of such conditions, the Water Bureau appealed many of the vital requirements, further jeopardizing their fate, leading to today’s hearing at 2pm, and quite possibly, a further appeal if the City Council grants the Water Bureau’s wish.

It seems to me that a historic preservation organization such as Restore Oregon should be advocating in support of such efforts to preserve them, rather than taking a fatalistic position, especially at this key juncture. That alone raises many questions about the timing of this piece. Can you explain how it was decided to write this piece at this time? What was the process? Who initiated it, and why?

Thank you.

I would like to see someone at Restore Oregon’s organization answer Steve Reinemer’s questions….and not the intern. Who did the intern speak with to obtain this hazy description of why our National Register of Historic Places in a Historic District (WA Park) perfectly working sustainable open air reservoirs are being destroyed and dismantled? As Steve said, you should be advocating to RESTORE and PROTECT our reservoirs and yet you give an intern this assignment and although she probably worked really hard on this article, it isn’t pleasing anyone but the City and its contractors to read it.

1. I am baffled that some commenters to this article have mis-characterized its content. This article was intended to provide a broad overview of historic water-based resources and encourage people who may not be aware of or appreciate them to learn more. It was clearly NOT intended to dissect the politics and science of water treatment options for Portland.

2. As a historic preservation organization, we lack the expertise to pass judgement on the science of water treatment, or determine whether all legal recourse has been exhausted to retain the reservoirs. We are reserving judgement on that, absent compelling documented evidence from those who DO have that expertise. As a small, over-stretched non-profit covering a very large state, we must focus on our core mission. Restore Oregon is not afraid to take a stand on a topic for which we are subject matter experts.

3. Quit bashing our intern, and by inference, our management. Its just rude. Everything we publish on line is reviewed by our staff no matter who wrote it. How often does insulting an organization succeed in rallying them to your cause?

Just to be clear, I am the Executive Director of Restore Oregon and we are now closing comments to this article.