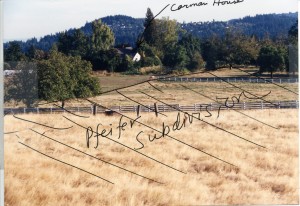

(Photo courtesy Lake Oswego Library)

Since 2012, the Lake Oswego Preservation Society has spearheaded a community-wide effort to save the oldest and arguably most historically significant house in Lake Oswego, the 1855 territorial-era Carman House. Representing one of just a small handful of pre-statehood properties that still stand in the Willamette Valley, just a few weeks ago the local landmark was destined for the landfill…. An 11th hour appeal may save it and set a precedent for countless other historic places across Oregon.

In mid-2013, the owner of the Carman House submitted an application to remove the local landmark status that had been imposed on the property in 1990. This application was based on Lake Oswego city code criteria for delisting a landmark property. In the late summer, the owner’s attorney changed course, submitting a landmark removal request based upon a little-known state statute commonly referred to as the “owner consent law.” The law, ORS 197.772, reads as follows:

A local government shall allow a property owner to remove from the property a historic property designation that was imposed on the property by the local government.

In November, the Lake Oswego Historic Resources Advisory Board unanimously decided not to remove the historic designation on the basis that the current owner was not responsible for the original objection that occurred nearly a quarter of a century ago. The owner appealed the Advisory Board’s decision to the Lake Oswego City Council.

In January, the Council, in a 4 to 3 vote, overturned the Advisory Board’s decision, removing the local landmark designation and clearing the way for demolition of the house to make way for redevelopment of the 1.25-acre property. The Council’s decision was made on the basis that the original objection to the designation stays with the property, not with the specific owner. Having already spent $10,000 in legal fees, the Society was out of options.

development. If the Carman House is demolished, it is

expected that the remaining 1.25-acres of the original

Donation Land Claim will be also subdivided and

developed (Photo courtesy Lake Oswego Library)

Until now. With the help of Restore Oregon, an attorney has volunteered to appeal the City Council’s decision to Oregon’s Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA). LUBA is a three-member board that hears and rules on appeals of land use decisions made by local governments. The Board has several months to hear the case and an appeal alone does not prevent the property owner from obtaining a demolition permit in the meantime (a motion requesting a stay of demolition must be filed and, if granted by LUBA, a $5,000 cash bond will be required).

Unless the decision is appealed to Oregon’s Court of Appeals, LUBA will once-and-for-all determine the fate of Lake Oswego’s oldest house, while also setting a precedent for how other jurisdictions allow for the removal of local historic designations (properties on the National Register follow a separate process to be removed from listing).

So, what have Lake Oswego’s tireless advocates learned?

- Never give up hope. The pro bono attorney who undertook the LUBA appeal committed to do so on the Saturday before the Tuesday filing deadline! This news came on the heels of countless rejections from other attorneys who had a conflict or could not spare the time.

- If possible, lay the groundwork before a preservation crisis develops. Build the organization’s relationship with the media, local government officials, and other non-profits. Show support by partnering with and joining other organizations as members. When you need allies, you won’t need to hastily educate them about your organization and its mission.

- There are more people that support you than you realize. Once you start publicizing the issue, you’ll find those who support your cause and your organization. Conversely, there will always be those in opposition so just take that in stride. You can’t please everyone.

- Keep a sense of humor. Our current theme song is: “Happy Days are Here Again.”

With apologies to Irving Berlin, our former theme song was, to the tune of “Heat Wave,”

I’m having a breakdown

A psychological breakdown

The anxiety’s rising

It isn’t surprising

It certainly hit the fan, fan - Be proactive. Know your community’s building and development code and seek to strengthen protections for historic properties, locally and statewide, before applications for delisting or demolition are submitted.

The Carman House as it appears today

(Photo courtesy Justin Runquist/Oregonian) - When testifying before hearing bodies always keep the focus of your testimony on the criteria and resist the temptation to dwell on emotional responses. Do your homework and don’t assume that all pertinent facts will be included in the staff report. Make sure that all documents that support your arguments are entered into the record. No new information can be introduced on appeal.

- Recognize that a long and intense battle can have a negative impact on your personal life. A campaign like this one, that has already spanned six months, can take a toll on you and your family members. Historic preservation activism is not for the faint of heart.

- There is always an “up” side, regardless of the outcome, including more awareness of the community’s history, increased visibility and membership for your own organization, as well as stronger partnerships with other groups. Celebrate your successes and make note of what you can improve on next time—because there will be a next time.

- Use the power of the media. Although the developer vs. the preservationist story may seem old hat, it’s the local specifics that make it newsworthy. Although obvious, it bears repeating that you should use all media at your disposal—local television stations, local and statewide newspapers, editorials, Twitter, Facebook, the organization’s own website, newsletter, and email blasts, etc.

- Legal battles are costly so you can’t fight all of them. As they say, “pick your battles.” If a legal defense fund has not already been established, create one and solicit donations in every way possible, including online fundraising tools such as fundrazr or gofundme. Raising money is critical to waging a successful campaign because the opposition often has very deep pockets. Keep in mind that it’s more about purse strings than heartstrings.

- Recognize that the land use public hearing process is, by nature, adversarial – you either testify for or against the application. Although it has yet to come about in this instance, the Society has successfully worked out solutions when both sides came to the table to brainstorm business-friendly solutions that would involve retention of a historic structure. This also gives you the opportunity to discuss benefits that the owners may not be aware such as placing the house on the National Register of Historic Places. If the owners are non-responsive, don’t give up, simply ask again.

- Be flexible in searching for solutions outside of the land use hearing process and make sure to explore all of your non-legal options. For example, meet with City officials to determine if the City would be willing to purchase the endangered historic property either as a community asset or to protect and resell it. Also investigate repurposing the structure; relocating it, including use as a possible secondary dwelling unit; and deconstructing it and storing it for potential rebuilding on a different site. If all else fails, try to gain access to thoroughly document the property so there is a record for future historians.

LUBA is expected to hear the Carman House case sometime in the spring.

One Reply to “Next Stop LUBA: Lessons Learned from the Carman House”

Comments are closed.