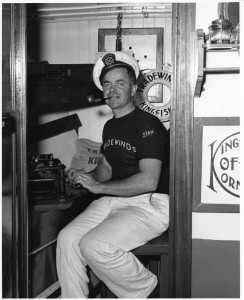

Coast Guard days

(Image courtesy of

Lincoln County Historical Society)

On December 5, 2013, it took just minutes for a “long reach excavator,” a jawed demolition machine, to destroy the Tradewinds Kingfisher, a National Register of Historic Places listed charter fishing vessel. In its heyday the Kingfisher may have been the most famous boat in Oregon.

A case study of the Tradewinds Kingfisher preservation efforts may prove enlightening to those contemplating saving a historic boat or structure.

Built in 1941 at Westerlund Boat and Machine Works in Jantzen Beach, Oregon, the 50 ft, all wood, Kingfisher, was steeped in Oregon history. Just months after Kingfisher owner, and skipper Stan Allyn (1913-1992) took possession of his new boat, the US entered World War II. Allyn offered the Kingfisher up for wartime use. The Coast Guard used Allyn’s new boat as a boarding craft and to patrol for a possible attack from Astoria to Coos Bay. At the war’s end the Kingfisher returned to Allyn and its Depoe Bay homeport.

Always brightly painted, flamboyantly signed, and much larger than all of Depoe Bay’s charter boats, the Kingfisher appears in thousands of tourist’s snapshots, home movies, and picture postcards. Allyn utilized all kinds of marketing innovations on the Kingfisher: a swing suspended high above the deck, girls in bikinis, deckhands in snappy uniforms, and a pulpit that afforded passengers the thrill of being in front of the bow.

Allyn was also a maritime writer and,

for a time, a coastal correspondent

for the Oregonian. Supposedly he did

much of his writing aboard the Kingfisher.

This photo is LCHS #2695

(Image courtesy of

Lincoln County Historical Society)

Listed on the National Historic Register in 1991, the Kingfisher was retired in 2000. Its 1950s diesel engines were no longer fast enough to cover the long distances needed for cost effective fishing and whale watching expeditions. In 2001 the Lincoln County Historical Society accepted the Kingfisher as a donation knowing it lacked the means to properly curate the boat, but with hopes of attracting additional public support. In addition to its preservation, long-term goals included offering bay tours aboard the historic vessel.

Unfortunately the Kingfisher’s rich history failed to capture the public’s imagination and garner support. The donation came with some “baggage” that hampered promotional efforts. A segment of the local population felt acrimony towards owner Stan Allyn, a tireless promoter in a highly competitive business. His brazen promotional efforts came at the expense of some of his competitors. There also exists a longstanding socio-economic divide in Lincoln County between charter fishing boat operators such as Allyn and commercial fishermen. When Stan passed away in 1992, any remaining less-than-positive feelings were inexplicably re-directed at his boat.

(Image courtesy of Lincoln County Historical Society)

Geography further challenged preservation efforts. When the Society acquired the Kingfisher, Depoe Bay moorage was not feasible. The Kingfisher was moved to Newport then to Toledo, thus creating a disconnect from its homeport.

Over the years a very small group of businesses and individuals donated time and materials to maintain the Kingfisher. The Kingfisher required a minimum of $15,000 annually in maintenance, repairs, and moorage fees – far exceeding the Historical Society’s annual budget for curating the other 40,000-plus objects in its collection.

When I came on board as director of the historical society in 2011 a shipwright’s survey was setting on my desk indicating the Kingfisher needed over $70,000 in repairs. Feature length articles in the local papers about the plight of Kingfisher received no response. By 2013, in danger of sinking and creating an environment hazard, the historical society’s Board of Directors voted unanimously to dismantle the Kingfisher.

(Image courtesy of Lincoln County Historical Society)

Perhaps the dominate lesson of the Kingfisher is that historic significance in of itself is not enough to sustain a preservation effort. Broadbased public support, which the Kingfisher lacked, is essential. The close connection of the Kingfisher to its outspoken owner, a geograpical disconnect from it homeport, and it association with a non-dominant, charter fishing, industry all made saving the Kingfisher an uphill battle. At the same time these are the things that made the Kingfisher, the Kingfisher.

Prior to demolition, parts were removed for a future exhibit and the exterior of the boat scanned using 3D laser technology. The laser scan produced a very exact electronic record for use by future researchers, model builders, and boat builders. The Society also maintains a sizable archival collection of Kingfisher photos and documentation.