By Janice Dilg

This year marks 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment added voting rights for most women to the US Constitution. Many Oregon women had been voting since 1912 when the word “male” was removed from voting qualifications in the state constitution. By 1920, women in Oregon had been voting for eight years, as well as running for, and being elected to, government office. In 1920, the Oregon Legislature met in a special session to ratify the 19th Amendment. Both chambers unanimously approved House Joint Resolution No. 1 introduced by Rep. Sylvia Thompson (D-The Dalles), and on January 14, 1920 Oregon became the twenty-fifth state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

![]() The person most Oregonians associate with the struggle for women’s voting rights is Abigail Scott Duniway, often called the “Mother of Equal Suffrage.” In 1871, Susan B. Anthony accepted Duniway’s invitation to visit the Pacific Northwest to energize the suffrage cause here. That same year, Duniway launched her newspaper The New Northwest to provide her a platform to promote women’s rights, particularly voting rights. As the two women toured the region, Anthony mentored Duniway on the art of public speaking, and how to handle the inevitable hecklers. Abigail Scott Duniway would remain intimately involved in state, regional, and national suffrage movements throughout her life.

The person most Oregonians associate with the struggle for women’s voting rights is Abigail Scott Duniway, often called the “Mother of Equal Suffrage.” In 1871, Susan B. Anthony accepted Duniway’s invitation to visit the Pacific Northwest to energize the suffrage cause here. That same year, Duniway launched her newspaper The New Northwest to provide her a platform to promote women’s rights, particularly voting rights. As the two women toured the region, Anthony mentored Duniway on the art of public speaking, and how to handle the inevitable hecklers. Abigail Scott Duniway would remain intimately involved in state, regional, and national suffrage movements throughout her life.

In 1872, the women’s suffrage movement adopted a strategy titled the “New Departure” claiming voting rights for women based on the 14th and 15th Amendments. Abigail Scott Duniway, Maria Hendee, Mary Ann Lambert, and Black suffragist Mary L. Beatty tested that strategy by attempting to vote in downtown Portland at the Morrison Precinct. The precinct judge took their ballots and placed them under, not in, the ballot box. Undeterred, Duniway, Beatty, and other suffragists formed the Oregon Woman Suffrage Association in 1873 to their struggle for women’s voting rights.

The Portland Hotel figured into women’s suffrage events for many years. Susan B. Anthony stayed there when she was the featured speaker at the 1905 National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention held at First Congregational Church. At a luncheon held at the hotel in September 1912, long-time suffrage leader, Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy launched the innovative Everybody’s Equal Suffrage League. Designed to engage working women in the cause, lifetime membership cost a modest twenty-five cents and all members were vice presidents!

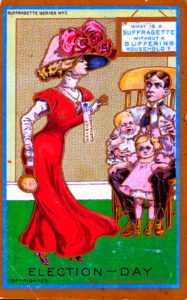

Oregon men voted six times on the issue of women’s suffrage—1884, 1900, 1906, 1908, 1910, and 1912—the most of any state in the nation. While pro-suffragists continually brought the issue to ballot box, there was an equally dedicated organization of anti-suffragists opposing them every time. The ponderously named Oregon State Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women was comprised of a small number of well-funded, elite women. Three such ardent members—Eva Bailey, Katherine McCamant, and Alice Heustis Wilbur—served as the public face of the organization. They claimed women: did not want the responsibility of voting, and they would neglect their domestic duties going to vote. They considered the continued failure of woman suffrage at the ballot box made their point.

By 1912, Abigail Scott Duniway had fallen seriously ill and was inactive during that final campaign. Younger suffragists, impatient with Duniway’s “still hunt” style, seized the opportunity to run a “hurrah” campaign complete with public rallies, street corner speeches, and advertising in publications and movie theaters. The suffragist’s ultimate success rested on the broad new coalitions they built across the state between: multi-racial and multi-ethnic women’s groups, organized labor, granges, working-class women, neighborhoods, men’s equal suffrage leagues, and professional organizations.

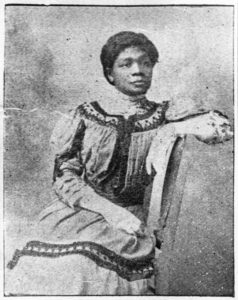

One key coalition player was Harriet “Hattie” Redmond. Her father Reuben Crawford was politically active and instilled the importance of that work in his daughter. As president of the Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage League, and a leader in the State Central Campaign Committee in 1912, Redmond spoke regularly of the value of the vote, especially to Black women. Redmond and Lovejoy held joint events at Redmond’s church, Mt. Olivet First Baptist Church; then located next door to the Golden West Hotel.

Every corner of Oregon had its own equal suffrage organization in 1912—from Astoria to Vale and Gladstone to Klamath Falls. State and national leaders shared campaign materials in support of local efforts. The poster held by one woman in the cover photograph is from the successful 1911 California suffrage campaign. National suffragists traveled to Pendleton in 1912 to rally support for the ballot measure, and after women’s suffrage was achieved in Oregon, national suffrage groups kept strong connections here. As the image from the 1916 Pendleton Round-Up shows, national suffrage organizations understood that thirty-six states were needed to ratify a federal amendment, and they were counting on Oregon to be one of them.

As we reflect on the 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment, I encourage you to understand that the amendment was a beginning to women’s struggle for equality, not an end. It is also important to understand that voting rights did not extend to all women in Oregon in 1912 or to all women in the United States in 1920. Racist and xenophobic laws and policies ensured that Black, Native, and Asian American women did not effectively have the right to vote for decades, and for many women, and men, not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. As this election year unfolds we can see in real time the rights that suffragists worked so long and hard for—who does, and does not, have access to the ballot, and why voting is important—are still relevant and still worth fighting for.

To Learn More:

Oregon Women’s History Consortium: www.oregonwomenshistory.org

National Votes for Women Trail: www.nvwt.org

Oregon Encyclopedia: https://oregonencyclopedia.org/