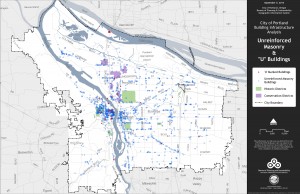

In the beginning of the twentieth century, as Portland grew and expanded to the east and north, residential and commercial buildings were constructed along the streetcar and automobile travel corridors and at neighborhood centers. Many of these utilized unreinforced masonry (URM) for its improved fire resistance, durability, and lower maintenance over wood framing. The City does not have a good knowledge base of these buildings, their economic status, or their safety considerations.

in St. Johns neighborhood, Portland

(Photo courtesy Rob Dortignacq)

(Photo courtesy Rob Dortignacq)

(Photo courtesy Rob Dortignacq)

(Map courtesy City of Portland)

(Photo courtesy Masonry Building Survey Project)

A study was initiated during the spring and summer of 2013 of those buildings as found on a compilation of various URM inventories within selected, but representative, neighborhood commercial areas. Supported by the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability and funded by the State Historic Preservation Office, the 62-page study surveyed 450 properties, explored case study examples, and recommended policy changes to better address Portland’s URM buildings.

This week, study author Rob Dortignacq shared his findings and recommendations with Restore Oregon.

Characteristics and Observations Extracted From the Study

- The existing inventory was fairly basic and had limited building data. This was expanded to include more architectural information.

- The inventory data was old and had been assembled from a variety of sources. Its current validity was found to have errors attributed to building replacement or demolition, data entry, mapping, and insufficient knowledge of the construction.

- Some buildings are historically significant, while others are of recent vintage or are not historically or architecturally significant.

- Most buildings are smaller sized, of one or two stories in height, most are used for commercial purposes or for mixed commercial – residential use. There was also a sector of much larger residential structures.

- Improvements in technology and construction changed the construction over time. A great variety of construction materials including brick, clay tile, a significant amount of concrete block, and board formed concrete can be found in these buildings. Roof and upper floor framing is typically wood.

- Many buildings have a variety of structural systems in place, the original systems have been modified, or new ones have accumulated over time from additions and alterations.

- A large number of buildings have coverings that conceal their exterior walls and structure that prevent easy or quick determination of their URM status or any seismic improvements.

- From the survey perspective, very few properties have been seismically upgraded. Many do not appear to have sufficient excess revenue to allow extensive retrofits. However, many of these could greatly improve safe exiting with minimal costs.

- The few properties that were seismically retrofitted were the ones that had full building rehabilitations that also greatly upgraded their value and sometimes increased space or number of occupants.

- Some properties have been remodeled over their life, particularly the ground floor levels as tenants have come and gone. These improvements often do not require a building permit. As a result there are a number of properties that have tenant upgrades to meet the current market and create increased revenue, but do not improve the seismic capacity of the masonry.

- There are a number of ordinary, non-historically significant, sale and service type structures. These buildings tend to be detached and are in good condition. For these buildings the seismic upgrade costs might not be high. However, in economically strong neighborhoods, it is more advantageous for the owners to rebuild with a new and potentially larger structure.

- Similarly, there are abundant historic structures that are modest and in fair condition found throughout all of the study areas. The cost of upgrading these buildings is relatively high for their comparative value and income return. Many of these will simply be replaced when the situation presents itself.

- The large, taller residential masonry buildings are typically well maintained and fully occupied, but are seismically the most hazardous.

Considerations and Strategies for Rehabilitation and Seismic Improvements

Survey & Inventory

- Consider all historic buildings vulnerable to replacement, particularly in economically prosperous areas. Additional windshield survey and inventory work should be directed primarily toward potential historic resources.

- The most historically significant buildings should be ‘earmarked’ for a full rehabilitation strategy, either phased or all at once. This would give the opportunity to install new mechanical and electrical systems, and tenant improvements while the seismic work is completed. This requires a motivated owner.

- New inventory data should have expanded information including construction materials, number of stories, and condition. Seismic upgrades should be noted in the data base as they occur.

Policies

- Focus policy revision efforts toward success in renovation and seismic retrofit of historically contributing buildings.

- Develop alternative and flexible strategies, and allow phased work to increase participation.

- Avoid mandatory seismic upgrade requirements unless there are accompanying financial or regulatory incentives.

- Allow an owner who is interested in voluntary seismic upgrades an ‘amnesty’ from other planning, building, or bureau requirements in order to simply accomplish that task.

- Partner with the insurance industry to develop insurance premium incentives for seismically improved buildings.

Code

- Require a percentage of the proposed construction costs be devoted to specifically to seismic upgrades.

- Emphasize a life/safety approach considering the actual degree of hazard and using techniques to ensure safe exiting or safe haven.

- Revise the normal procedure of requiring full upgrades when there is an occupancy change particularly if it is at the same relative hazard level. Provide a more flexible approach and allow a phased seismic upgrade strategy.

- Develop cost effective strategies for low hazard, low occupant buildings. If these building are damaged by an earthquake, the damaged areas can typically be reconstructed easily, and then be built to meet current codes.

Incentives & Education

- Consider a recognition system for seismic upgrade efforts as a method to convey the increased safety to occupants and potential renters. Compare what could be done for buildings to how auto manufacturers promote their new vehicle safety features.

- Provide educational material for the multi-story residential masonry building owners. Utilize successful rehabilitation stories from other properties. Work to promote incremental, phased upgrades specific to each building. A method that can work for an apartment complex is different than that for a condominium complex.

- Create a capital fund pool and use it to assist historically significant properties with voluntary seismic upgrades each year. This could be funded by matching grants or long term loans or a mechanism that minimizes the immediate financial impact.

Editor’s Note

The study was authored by Rob Dortignacq and Kim Lakin. More information on the project can be found on the Oregon Heritage Exchange. A 2012 Restore Oregon report, Resilient Masonry Buildings, called for studies such as this to be conducted across Oregon.