Neighborhood was purchased in April in part

because of the presence of historic lot lines

(Photo courtesy Portland Chronicle).

While the rebounding economy and influx of new residents has left no shortage of opportunity or incentive for developers to tear down and replace older houses in Portland’s single family neighborhoods, a recent trend indicates that an arcane provision in the City’s Zoning Code is among the biggest threats to the fabric of Portland’s older neighborhoods.

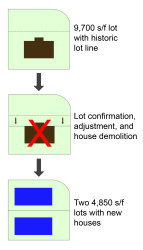

The practice of “lot confirmation”— petitioning the city’s Bureau of Development Services to recognize long-forgotten underlying lot lines in order to split an existing tax lot— effectively circumvents established zoning regulations and allows developers to establish smaller-than-standard lots in single dwelling zones.

lot line adjustment,

and demolition of an

existing home make way

for two new houses.

Portland’s single dwelling zones dictate that only one house can be built on a given amount of land. For example, the R5 zone (the most common zone for Portland neighborhoods) specifies a maximum density of only one unit of housing per 5,000 square feet. The lot confirmation loophole can be exploited to produce buildable lots as small as 1,600 square feet in the R5 zone, adding an economic incentive to remove an existing home in favor of multiple skinny houses.

Single family homes in older neighborhoods are particularly vulnerable to being lost to this practice, as underlying lots generally reflect lot lines drawn on planning and plat maps developed a century or more ago. Historically, it was common practice for developers in newly-platted neighborhoods to offer small lots to buyers, with the intention of combining two or more small lots to form one tax lot. For example, some neighborhoods consist largely of 25-by-100 foot underlying lots combined upon purchase to form tax lots 5,000 square feet and larger. While the smaller lots were not generally intended to stand alone as full tax lots, today’s real estate boom has reopened this largely forgotten door.

October 4 to make way for two houses on 4,850

square foot lots (Photo courtesy Eastmoreland

Neighborhood Association)

In 2013— the last year for which the City has available data— 65 homes were demolished to make way for lot splitting through the lot confirmation process. As is the case with virtually all demolitions occurring in single dwelling zones, the density gains resulting from these teardowns was nominal (these 65 demolitions yielding a net gain of only 72 units in 2013). And while the map below illustrates the extent of the problem, to date there has been no definitive count of the total number of lots that could be split through lot confirmation (one estimate is that up to 13,000 properties could be at risk).

In response to concerns raised by Restore Oregon and others, on October 6th it was announced that the City’s Residential Infill Project will consider lot confirmations as part of the project’s comprehensive rethink of the city’s single dwelling zoning.

Additional information on lot confirmations can be found at the Portland Chronicle and Fix Portland Zoning.

Visit our Neighborhood Preservation page for more information on demolitions in Portland.

A citywide map has been made available by the Portland Chronicle.

One Reply to “Zoning Code Loophole Contributes to Demolition Pressure”

Comments are closed.

Thanks. Good article.

What would it take for the City to close this loop hole? Is it possible for Council to consider the contradiction that this loophole poses (as it violates what they say are the criteria for density in particular areas according to the comprehensive plan), without waiting for the next major code revisions? I don’t know much about it, but I assume they balk at changing code in a piecemeal way, even if the loophole is causing great damage (which it is).

Just wondering if in your study of this you have insights about what they require in order to make a change? …Years of study? …Blue Ribbon Committees? Or can the Council instruct staff to research the issues, present pros and cons, hear testimony…and then make a decision? I know they do this in other policy areas…

thanks,

Trudy